Orvieto between Art and History

Orvieto

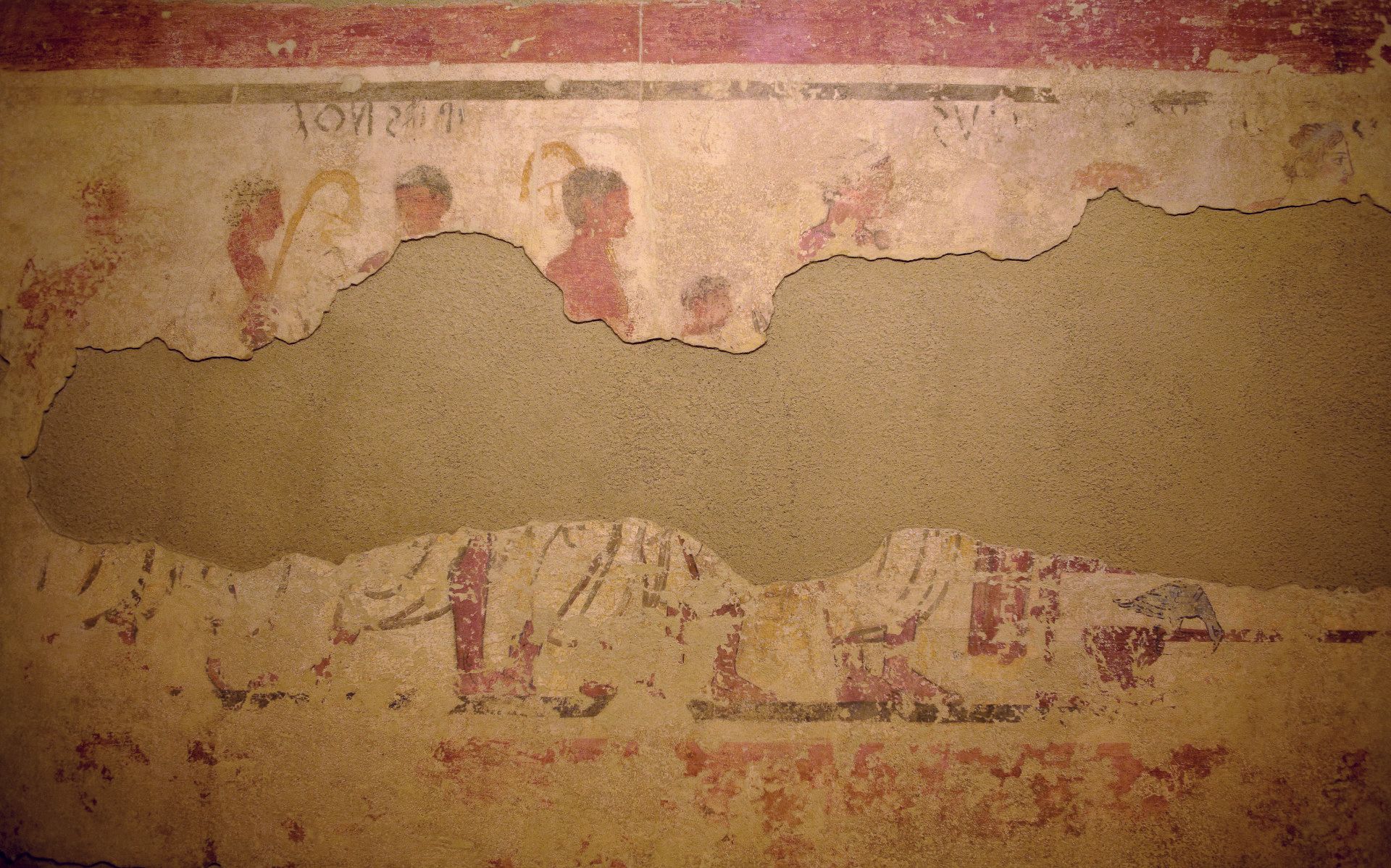

VOLSINII (ORVIETO) ANCIENT CAPITAL OF THE ETRUSCAN STATE

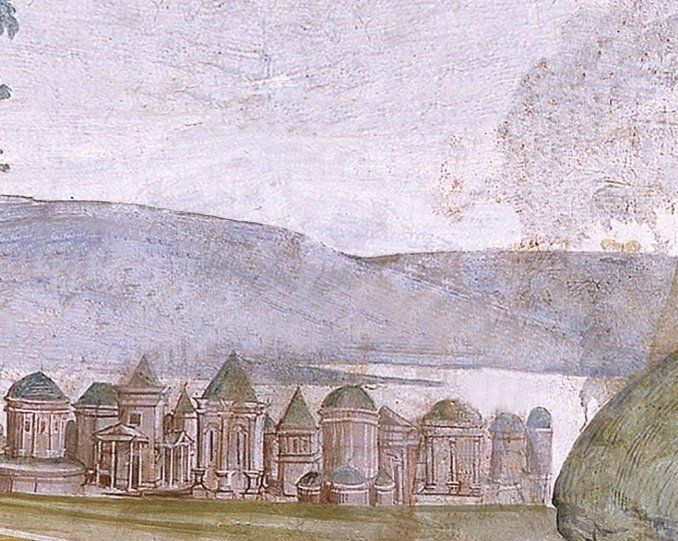

ORVIETO AND THE CATHEDRAL

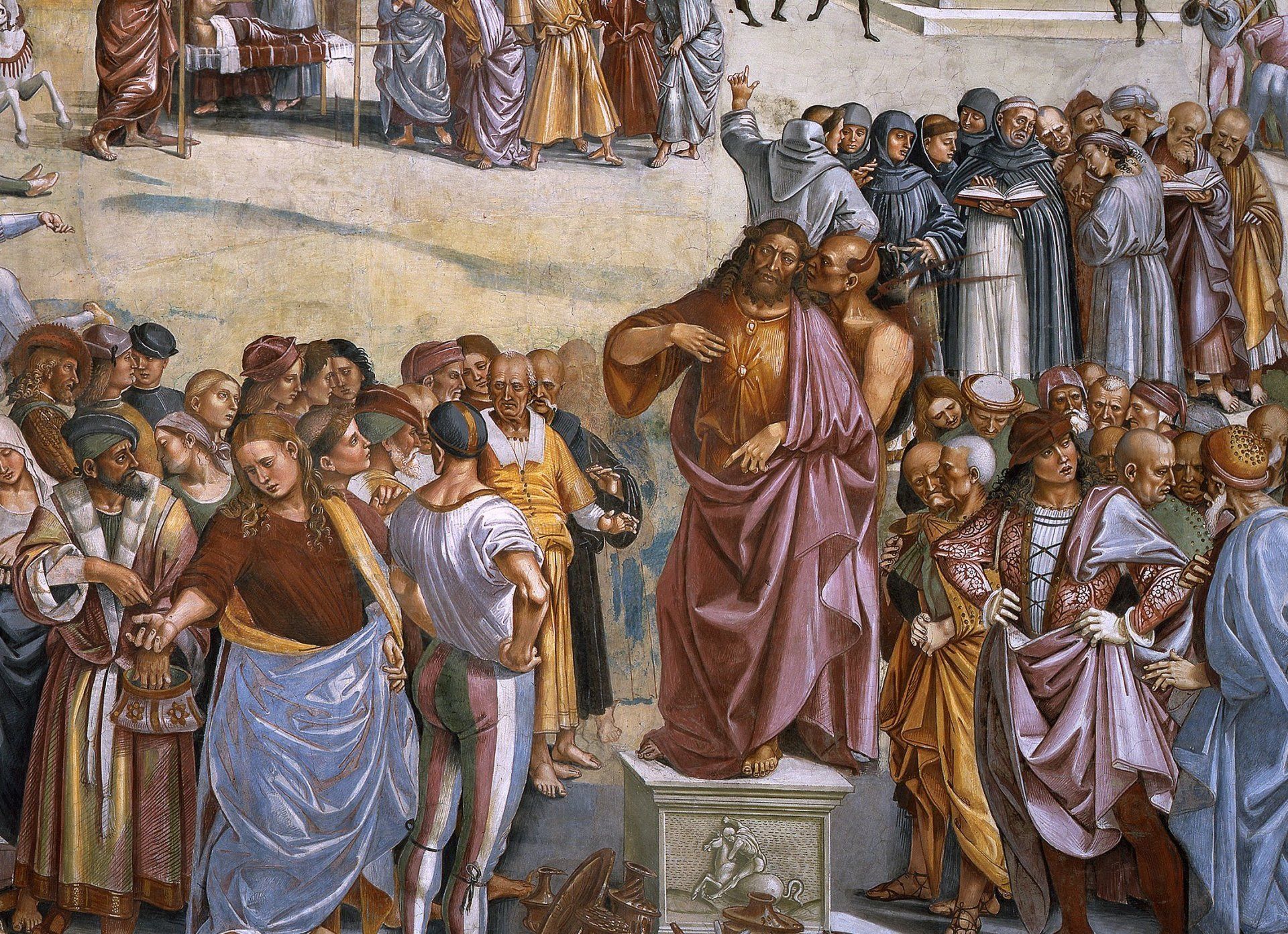

LUCA SIGNORELLI (CORTONA 1445 - IVI 1523)

LORENZO MAITANIARCHITETTO 1270-1330

Lorenzo Maitani, architect and sculptor, was born in Siena in 1270,

son of the sculptor Vitale di Lorenzo called Matano. In 1310 he was called to Orvieto

by Pope Boniface VIII and appointed master builder of the Cathedral, a position he held until his death, in Orvieto in 1330. He designed the facade, developed according to a distinctly Gothic model, new and original compared to Italian and European types. Already before 1310 he had gone to Orvieto on several occasions to strengthen the unsafe construction of the cathedral. He interrupted his stay in Orvieto in 1317 and 1319-21 to repair the aqueducts of Perugia, in 1322 to give his opinion on the continuation of the work on the cathedral of Siena and in 1323 on the planned construction of the castle of Montefalco, in 1325 to restore the castle of Castiglione del Lago.

From the document of 1310 in which Lorenzo is designated “universalis caput magister” of the Orvieto cathedral, it appears that he was charged with building the facade and supervising its sculptural decoration.

Two drawings of the façade in the cathedral museum illustrate the genesis of the Maitanese project, which from a verticalism derived from the French Gothic architecture of the Île-de-France, passed to a more refined and balanced conception. This compromise between the French and Italian spirit and aesthetic principles is also felt in the wonderful reliefs that cover the four pillars of the façade.

The four bronze angels in the act of lifting the edges of the canopy that protects the marble group of the Madonna and Child placed above the central door, and the four symbols of the Evangelists, also in bronze, protruding above the cornice that runs along the pillars of the facade, give a very clear idea of the sculptor's depth;

Due to their affinity with them, the reliefs of the three lower zones of the first pillar, which go from the Creation of the animals to the Expulsion of the progenitors from Paradise, and the reliefs of the two lower zones of the fourth pillar with the Resurrection of the Dead, Hell and the ranks of the elect and the reprobate, can certainly be attributed to Maitani.

In his reliefs, Maitani has a well-defined personality which ensures him a prominent place in Tuscan sculpture of the fourteenth century.

His profound knowledge of the anatomy of the human body is coupled with an exquisite sense of linear eurhythmy, strengthened by French influences, which bends the transparent and light garments into a soft flow. And it is precisely this calm and serene lyrical spirit that distinguishes him artistically in the history of architecture and sculpture.

THE BEAUTY

Kalón means everything that pleases, that arouses admiration, that attracts the gaze. Beauty is almost always associated with other qualities.b Hesiod (Marriage of Cadmus and Harmony): “Whoever is beautiful is dear, whoever is not beautiful is not dear”. The oracle of Delphi, when asked about the criterion for evaluating Beauty, answers: “The most just is the most beautiful”. According to mythology, Zeus would have assigned an appropriate measure and a just limit to every being: the government of the world thus coincides with a precise and measurable harmony, expressed in the four mottos written on the walls of the temple of Delphi: “The most just is the most beautiful”, “Observe the limit”, “Hate hybris (arrogance)”, “Nothing in excess”. The Greek common sense of Beauty is based on these rules, in accordance with a vision of the world that interprets order and harmony as that which places a limit on the “yawning Chaos”, from whose throat, according to Hesiod, the world sprung.

The Orvieto Rock was born about three hundred thousand years ago following the eruption of the Monti Volsini volcanic complex.

Orvieto, a thousand-year-old city suspended between heaven and earth, has revealed another aspect that makes it unique: a maze of caves is hidden in the underground darkness of the cliff.

The geological nature of the boulder on which the ancient Etruscan Velzna (later Volsinii) stands today, has allowed

the inhabitants to dig, over the course of the millennia, an incredible number of cavities, caves, wells, cisterns and tunnels that extend, overlap and intersect beneath the modern city.

The stratigraphy conditioned the circulation of underground water and over the millennia, the inhabitants of the Rupe operated in such a particular way in the subsoil of the city, to the point of digging over 1200 caves.

The need for water supply was therefore probably the reason that gave the go-ahead

to underground constructions.

La Rupe, colonized as early as the 9th century BC, saw the prosperity of one of the most important Etruscan cities, the ancient Velzna. The first hypogea dug by man in search of water date back to this period, an irreplaceable resource in a city that, impregnable due to the rock walls that defended it, had to be able to resist sieges.

The Etruscans built ingenious cisterns for the conservation of rainwater as well as an extensive network of tunnels for its conveyance and very deep wells (with a rectangular section measuring no more than 80 by 120 centimetres) which, having overcome the permeable layers, reached the water table. Thanks to all this, Velzna (then Volsinii, today Orvieto) managed to achieve self-sufficiency for water supply, so much so that it fell into the hands of Rome, in 264 BC, only after having resisted a siege that lasted almost three years.

In the Velzna underground, many “dovecotes” were also built where carrier pigeons could enter and exit to carry out their task.

In the subsoil there are the remains of an entire medieval mill (the mill of Santa Chiara) complete with millstones, press, hearth and mangers for the animals used to grind the stones or an entire olive press, also complete with millstones, press, hearth and pipes for water and cisterns.

The Etruscans, founders of the city, made Velzna an example of modernity and organization

and was so rich that it was known by the name of Oinarea.